A new study led by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis finds that black carbon levels average 38% higher across new measurement sites in the Global South than current models predict.

The findings, published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications, highlight the gaps in current efforts to accurately measure the potent super pollutant, which degrades air quality, harms health and contributes to global warming.

The underestimated scale of black carbon levels in low- and middle-income countries underscores the urgent need for international mitigation efforts, alongside decarbonisation measures.

Why black carbon matters

Black carbon, often referred to as ‘soot’, is an important component of particulate matter that is released into the air by burning fossil fuels, biomass and waste. It is often emitted alongside other climate forcers, including CO2, carbon monoxide, non-methane volatile organic compounds and organic carbon.

The super pollutant is a public health threat linked to heart disease, respiratory illness, and cancer. It also absorbs sunlight and warms the atmosphere, accelerating global warming. It exacerbates snow and ice melting, monsoon and weather pattern disruption, flood risk and heat stress.

Black carbon has an estimated lifetime of just one to two weeks in the atmosphere, so reducing emissions can realise local and regional benefits almost immediately for people and planet.

Global blind spots affecting the most vulnerable

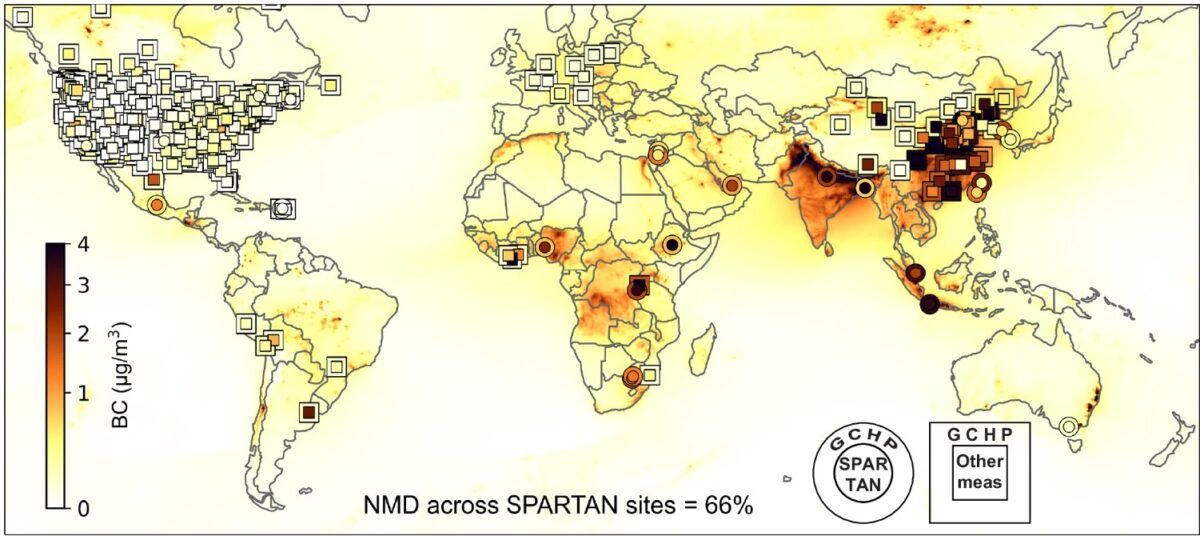

The study used long-term, globally consistent ground-based measurements from the Surface Particulate Matter Network (SPARTAN) to evaluate black carbon emissions. By linking these real-world measurements with high-resolution simulations from the global air quality model GEOS-Chem, researchers were able to evaluate how accurately current emissions inventories capture actual pollution levels across diverse sites worldwide.

They found a striking mismatch. While the model reasonably captured black carbon concentrations in high-income regions, it dramatically underestimated concentrations by up to fourfold in cities across the Global South, including Dhaka (Bangladesh), Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), Ilorin (Nigeria), and Mexico City (Mexico).

These underestimates may reflect outdated or incomplete data used in global emission inventories, which often rely on default assumptions from high-income countries. In many low- and middle-income countries, black carbon is primarily emitted from informal sources, like household cooking with wood or charcoal, open burning of waste, and poorly regulated industrial activity – sources that are rarely well documented.

Clean air action through better data

The research highlights the value of long-term, globally consistent measurements, like those from SPARTAN, for understanding pollution patterns and informing targeted action. But more research is needed for more accurate black carbon emissions factors to underpin modelling, target setting and regulation. Clean Air Fund is working with SPARTAN and partners across the Global South to strengthen monitoring capacity and support data-driven action for cleaner air. Addressing black carbon emissions is a crucial opportunity to achieve fast climate mitigation while delivering immediate health benefits to communities most affected by pollution.

Explore the findings

- Read the full study

- Learn more about SPARTAN

- Find out more about Clean Air Fund’s black carbon programme.