- The COVID-19 lockdown has led to cleaner air, but will do little to address the issue of air pollution in the long run.

- People living with poor air quality may be more susceptible to this disease, and airborne particulate matter may help to spread the virus.

- But world leaders now have a chance to plot a different, cleaner future.

As the coronavirus pandemic impacts millions across the world and brings economies to a grinding halt, there is a lot of talk about how emissions from fossil fuel combustion have dropped radically in many countries. Yet this is no solution to air pollution and climate change. For while eerily empty cities may be bathed in blue skies, millions are suddenly out of work and wondering how they are going to care for their families.

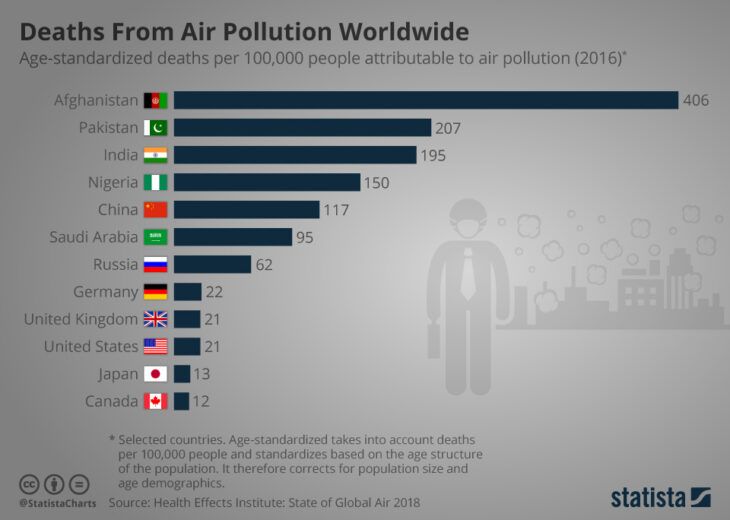

The poor and most vulnerable will suffer most from both the health impacts and the economic crisis. Cleaner air for a few months may be a tiny silver lining to COVID-19’s dark clouds, but will do little in the long run to solve the problem of outdoor air pollution that kills more than four million people every year. For that we need to kick our habit of burning coal, oil and gas.

What’s more, people living in high-pollution cities are more likely to have compromised respiratory, cardiac and other systems – and are therefore more vulnerable to COVID-19’s impacts.

One of the refrains all of us are hearing as the coronavirus spreads is to quit smoking. But what about the 90% of people worldwide who are exposed to high levels of air pollution? They can’t choose to quit breathing the air where they live. On every continent, people suffer the negative health impacts of air pollution. Living in Delhi is comparable to smoking six cigarettes a day. The respiratory systems of people in California and Australia have been compromised by air pollution from climate-fuelled forest fires. The people of Wuhan have suffered poor air quality for years, and just last summer took part in air pollution protests.

During the SARS outbreak in China, a study by researchers at UCLA’s School of Public Health showed that patients with SARS were more than twice as likely to die from the disease if they came from areas of high pollution. The same seems true of COVID-19: the more air pollution you are exposed to, the sicker you are likely to get.

And while it’s too early to prove a direct correlation between current high air pollution levels and incidence of COVID-19, high pollution levels might also increase the risk of contracting COVID-19 in the first place, as particulate matter has the potential to act as carriers for contagion leading to rapid spread over larger areas. A paper published by the Italian Society of Environmental Medicine suggests that “the rapid increase of contagion rates that has affected some areas of Northern Italy could be tied to atmospheric particulate pollution acting as a carrier and booster there”. A Harvard study has just found the first correlation between air pollution and COVID-19 deaths in the US.

The response to this pandemic also threatens to make air pollution’s health impacts worse in the longer-term. Several governments are moving under the cover of COVID-19 to give industry a break and weaken clean air standards. In the US, the Environmental protection Agency (EPA) is accelerating its radical relaxation of regulation as the pandemic proliferates. In South Africa, air pollution standards have been significantly weakened during lockdown and this will, according to South Africa’s Life After Coal Coalition, cause an estimated 3,300 premature deaths. There will be particularly profound health impacts on children, the elderly, pregnant women, and those already suffering from asthma, heart, and lung disease.

Some elected officials are taking a different tack. For instance, in Bogotá, Colombia’s capital city, facing a ‘triple threat’ of poor air quality, seasonal respiratory illnesses and the pandemic, Mayor Claudia Lopez opened 76 kilometeres of new bike lanes to reduce crowding on public transport and help prevent the spread of coronavirus while simultaneously improving air quality and people’s health.

As world leaders respond to the coronavirus, they have a chance to chart a different course and make a major intervention for a healthy planet and healthy people. With trillions of dollars in economic stimulus investments in the offing, they have a golden opportunity to channel significant portions of those funds to fast forward to a renewable energy economy. A transition to clean, renewable energy and transport will seriously reduce air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and the impact of future pandemics.

The coronavirus pandemic has made it clearer than ever that human and planetary health are intimately interconnected. The choice is ours to act accordingly.

This article was first published on World Economic Forum and is reprinted with permission.

A partnership with the World Economic Forum is in place to protect public health by mobilizing multi-stakeholder action on ambient air pollution. The Forum will build a cohort of leaders to catalyze corporate and political will; create a shared set of tools and facts for prioritizing actions; drive thought leadership; deliver concrete action as well as share lessons learned.